Scrap Metal Drive WWII — Courtesy of Bygonely.com

Legend has it that one of the first contracts the U.S. Continental Congress penned was for muskets, which were to be used in the Revolutionary War effort. The Founders then penned another for gathering the scrap metal needed to help supply the craftsmen that made the muskets.

Revolutionary War muskets (or long guns) were actually made from wood with metal parts, which included the steel bayonets.

However, it stands to reason that the newly created Congress pushed for weaponry and other war items to be manufactured from recycled material whenever possible: the fledging United States was cash strapped.

According to information at Recycle Nation, George Washington urged the reuse of worn chains from frigates, while Paul Revere advertised for scrap metal of all kinds.

The American Civil War also saw collection for recyclable materials for both the North and South. People donated church bells, steeples, pots and pans – anything that could be used for the war effort.

But other than wars, when the need for metal was great, Americans didn’t consistently recycle metal goods. In fact, when World War 2 began, an “estimated 1.5 million tons of scrap metal lay useless on U.S. farms – enough to build 139 battleships weighing 900 tons each, 750,000 tanks 18-27 tons each, or countless airplanes, weapons and other materials.” (Source)

War World 2: The nation collects scrap – and lots of it

The U.S. had a limited supply of steel when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor; the lack of supply was a distinct disadvantage as both “salvaged iron and steel were essential to the open-heath method of steel production,” writes Ronald H. Bailey in his piece, Iron Will: Scrapping History (reprinted on History.net).

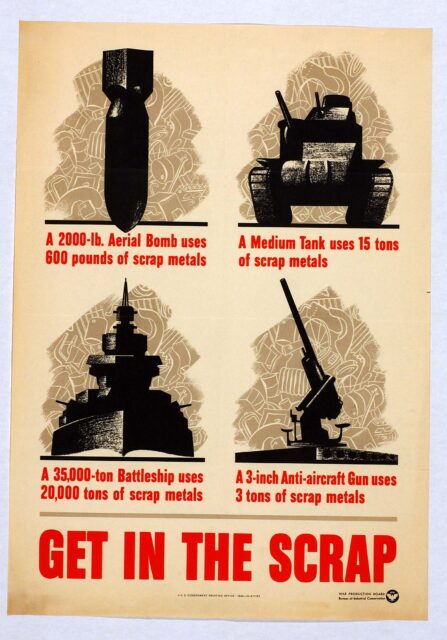

Due to the extreme need for these materials, the War Production Board launched the first nationwide scrap metal drive in the summer of 1942.

Scrap metal drives were held nationwide, and everyone was expected to participate – including children! Farmers, too, played a big role. They broke down the useless equipment and vehicles and donated old tools and other implements.

Anything made of metal was collected, including keys and license plates. Metals of all types were collected: Iron, steel, aluminum, tin, bronze, nickel, silver, and copper. In fact, when the U.S. diverted America’s copper output to military use, pennies were produced from zinc-coated steel.

Collecting license plates; WWII Scrap Drive – courtesy Bygonely.com

Scrap drives brought people and communities together and boosted morale: people believed they were supporting husbands, fathers, and sons who were fighting – a message communicated through posters and other means.

These scrap drives, however, had a downside: In his “Iron Will” piece, Bailey describes how people were so zealous, anything made of metal was collected, including historical items such as monuments, cemetery war medallions, and other items of note – much to historians’ dismay. One reason it’s difficult to find historical items dated pre-WW2 is because so much was melted down.

Removing an old wrought iron fence; WWII scrap drive – courtesy Bygonely.com

Scrap recycling today – a direct offshoot of scrap drives

Once the war ended, scrap recycling slowed down as people returned to normal life and the U.S. ramped up production of consumer goods. It wasn’t until the first Earth Day observance in 1970 that people became aware of recycling and its positive impact on the environment.

Today, it’s a common sight to see peddlers collecting metal scrap throughout communities and then selling their haul to metal recyclers. Towns and cities offer pickup of larger white and durable good items or allow drop off at designated collection areas; damaged and dead vehicles are broken down and recycled.

Most important, metal recycling is now essential to the United States and the global economy. According to the latest figures from ISRI, the U.S. steel industry relies on ferrous scrap as its largest single raw material input. Recyclers supply 70% of all U.S. produced steel and stainless steel made from ferrous and stainless scrap.